How A City-Wide Zoning Change Helps Affordability

More flexibility in zoning helps families share the value of land and incentivizes builders to create more homes.

Howdy Neighbour!

One of the more controversial recommendations of the Housing Strategy coming to a vote on September 14 is to change the default base zoning from allowing only single family homes to allowing row-houses (up to 4 on a lot). For clarity, this is still low-density housing, but it adds to the variety of housing throughout the city. You can read the City’s excellent one-pager (PDF) of what the proposed new default (R-CG) actually looks like, but here’s an example:

We’ve seen some concerning claims circulating that this change will somehow make affordability worse. This appears to originate from a landscape architecture professor at UBC who as far as we can tell has not published any peer-reviewed work on the subject of housing economics. His arguments are unfortunately full of holes and his ideas don’t seem to be widely accepted by serious economists.

So today we want to explain, as clearly as we know how, why we think changing the base zoning will help affordability, and why some folks might be misled down the other direction.

Before we do that, though, we are going to have to accept a few key premises:

For better or worse, there is a housing market that provides housing to the overwhelming majority of Calgarians. This means that the best way to manage the prices of market housing is to shape the market with incentives for builders. Since we don’t see the end of capitalism coming any time soon, the market will have to help supply the majority of new houses needed in Calgary.

Housing is a need, not a want or a nice-to-have. It’s one of Maslow’s basic needs, and is a human right. Under market conditions, people will pay as much as they can afford (if they have to) to house their families. This means that those without the ability to pay are excluded. As the market prices a growing share of Calgarians out, more families find themselves without affordable options. This is why the market needs to be shaped to stabilise prices alongside expanding non-market housing options. If we don’t fix market conditions, it will become increasingly difficult to help the growing share of Calgarians.

Yes, we’re putting on our builder hat for a second

Let’s consider a builder who has recently purchased a piece of residential property in one of Calgary’s older neighbourhoods. A typical house like this might be a bungalow built in the 1960s. The house has fallen into disrepair, and the builder wants to remove the current house and build new ones.

In the vast majority of Calgary today, that builder has just one choice: Build a single-family home in its place. Because builders are in the business of making money, they will crunch the numbers and build the most expensive home they think someone will buy.

With the proposed change to allow other kinds of homes, the builder now has a few more options. For example, they could build four row houses on the same lot.

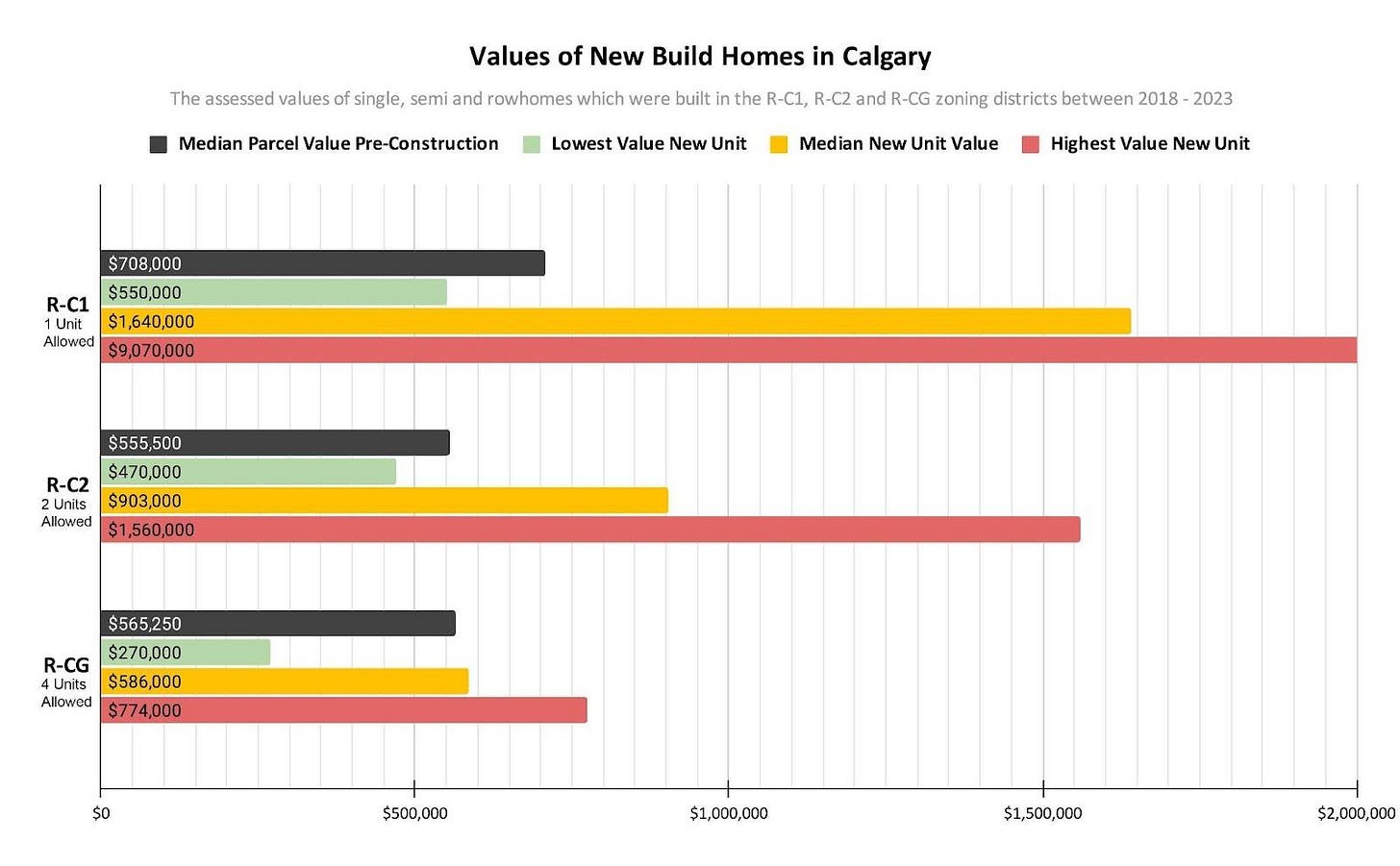

Calgary has statistics on how much new types of homes are valued at and how much the land costs, so let’s do an example with these numbers:

In the single-family (R-C1) scenario, a builder buys a lot for $708,000, builds a home, and sells it for a median price of $1.6 million. That’s a difference of $892,000 to cover the costs of building the house; any extra is profit.

In the contextual low-density (R-CG) scenario, a builder might buy a lot for $565,250 (these scenarios tend to happen on slightly less prime land than the single-family detached case), but build four row-house units. These units sell for $586,000 each, which leaves a buy-sell difference of just over $1.77 million, more than double the single-family scenario. It costs more to build four units instead of one house, but it doesn’t cost that much more. The incentive is there

And, as a bonus, there are now four houses on the market instead of one, and each of them are cheaper than the McMansion built in the single-family scenario. That’s four families housed instead of one.

The benefits don’t stop there, though: For the City, four units in a row do not cost four times as much to service: It doesn’t cost four times as much to collect garbage and recycling for example, and people living closer together makes transit cheaper and more effective. This four-unit plot of land is helping the city run more efficiently.

One-at-a-time rezoning ruins competition

So - with the example above, why doesn’t this happen more often? Well, for one it’s because changing land uses one lot at a time is a slow and uncertain process. It can take months before Council is able to review and discuss the change, and even then it might be turned down if enough angry people show up.

This slow, one-at-a-time process means that for a period of time, a set of row-home units might be one of the only options on the market.

Because this status quo has gone on for so long, we have a huge number of people who are interested in living in that type of house, and who may be desperate to find a place to live in the neighbourhood they want. Since housing is a need, people will bid and pay as much as they possibly can for a desirable place. Right now, the lack of choice means that any new variety comes at a premium.

But what would happen if these suitable places were available throughout the city? Instead of settling for a neighbourhood far away from family and friends, there would be options nearby. Instead of being one of hundreds bidding on a home, you might be one of only a few.

This is the key value that changing the base zoning brings: More options and competition throughout the city, and the ability for multiple families to effectively “share” the value of the land.

It also stops people from speculating on the value of the land. Suddenly, the available options for building these types of homes are far and wide. If you sit on a plot of re-zoned land hoping it might become steadily more valuable, you may lose out if many more of these units are built down the street or around the corner.

In Auckland, they did this and it worked

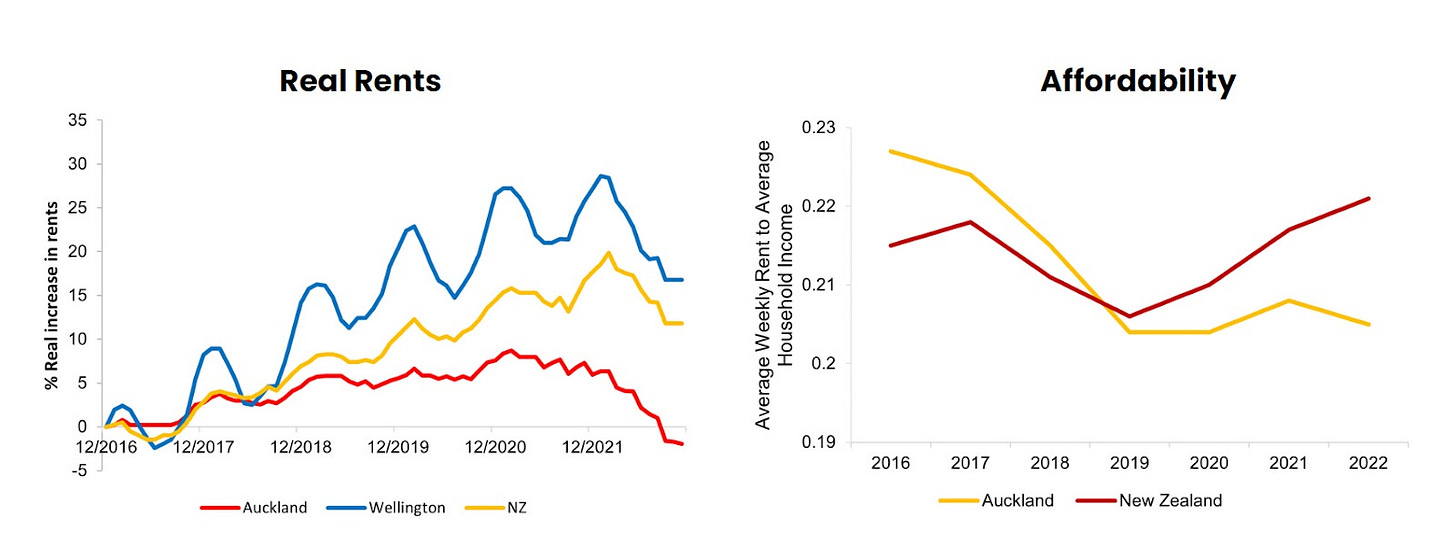

These examples aren’t just hypothetical: Auckland, New Zealand implemented a broad change like this in 2016 and the effects on affordability are very positive.

As this conversation about Auckland summarises: “The results aren't as simple as upzone, build more housing and prices go down, but they're also not too much more complicated than that”

We understand that this is a different city in a different country. But as far as solutions go, it’s pretty darn compelling.

So, in summary: Building modest, middle-class rowhomes instead of a McMansion allows for:

More people to share the value of that land, resulting in a lower house price

The addition of four times as many homes, allowing for more families to live where they want instead of settling for a more expensive or less-than-ideal location

Geographical competition by removing the “one-at-a-time” process that currently exists

Actual large-scale change due to incentives for builders

Limiting the tax increase because they are more efficient to serve by the City.

Affordability needs zoning, but that’s not all

The key thing to remember is that nobody is proposing changing the base zoning as a silver bullet. It will only work well when combined with other affordability measures.

This is why we need your support on September 14 and beyond. Tell your councillor that you support this smart change to R-CG and the rest of the recommendations.